Have you noticed that we’re stuck in the year of 1997? If you call recall that time, it was the apotheosis of neoliberalism with Bill Clinton securing a second term as US president and Tony Blair blustered into Number 10 riding the coattails of Cool Britannia culture and associated celebrities. While the presidents and prime ministers have changed, the socio-political fabric of capitalist realism has not. Furthermore, 1997 saw perhaps one of the most affective tricks used by the architects of this neoliberal peak to nullify critique. Because as Blair entered government, he set to task marketizing whatever of the artistic and cultural landscape was left over from Thatcher’s gutting of the Arts Council, creating the now artistically malignant, obdurately pervasive, and globally ubiquitous creative industries.

1997 therefore signalled the highly effective conquest of market ideologies within the cultural realm, and we have been paying the very high price – both figuratively and literally – ever since. That is because the paragons of this neoliberal profit-generating-machinic perfection knew all too well the power of the human imagination in creating alternative worlds. The artistic spirit and the political weapons it can wield needed to be tamed and domesticated in the service of extending neoliberalism’s reach into the cultural sphere. Neoliberalism’s goal is to rein in the artist, to give her no other option than to use her immense talent and skill to create surplus value that can be extracted. Hence, the practices of artistic production in the service of the radical imagination of a better, just, inclusive, common future, via political economic implements of austerity and a broader push towards ‘professionalisation’, became overwhelmingly redirected towards the reproduction of the neoliberal present day.

Art that is resistive, overtly political, subversive, or essentially cannot be appropriated into a neoliberal mindset is now, in the eyes of the system, merely a hobby; a quaint pastime that because it doesn’t have an immediate financial motive, can only really be tolerated so long as it sustains people to do other work that does. In essence, living in 1997 means that art is first and foremost a financial activity that replicates the social conditions of 1997 ad infinitum, and doesn’t err to realise any of the multiple possible post-capitalist futures that exist beyond that. You can be artistic as you please, as long as it paints a picture that already exists.

Technological lock-in

Of course, to suggest that we’re still in 1997 is absurd given our digitally connected world, right? The democratising technologies of the world wide web, planetary information and cultural systems, real-time news consumption, smart phones, and social media; they all wrought such a seismic shift to our creative and artistic sensibilities that surely, we’re beyond the analogue 90s? Sadly not. As Cory Doctorow aptly put it, the internet has undergone rampant enshittification at the hands of corporations that operate under the same neoliberal logic that smothered the world in 1997 (which incidentally, was the year that google.com was officially registered as a domain). Furthermore, the decreasing barriers to entry for creative work and artistic production that the digital revolution has brought about has simply ramped up the “hobbification” of the power of art. After all, anyone with a smart phone can call themselves a photographer, but all this does is decrease the ability of actual professional photographers to make a living through their art, and hence tightens neoliberalism’s hold over the reins of the artist.

And anyway, where has this supposed emancipating digital revolution led us? The unleashing of artificial intelligence and it’s highly deleterious impact upon art and culture. Many of the critics of AI bemoan how rather than the future we were promised of robots and AI replacing the manual work, domestic tasks and back-breaking labour so we can all enjoy a life of leisure, creativity and commonality, it has instead usurped the artist, the author, the musician, the filmmaker; those people who are at the forefront of imagining a better world. But surely, from the point of view of a capitalist realist, that is the very point! AI is the creation of the nonpareils of neoliberalism in the ideological crucible, Silicon Valley, so of course it will look to further nullify the human artistic imagination. Indeed, via AI’s incursion into art, the automation of the process of artistic appropriation has been totally perfected. Before the dawn of AI, neoliberalism had to expend valuable resources (in terms of policy diktats, resisting protests, implementing austerity on cultural institutions etc.) in marshalling artists into servicing the perpetuation of 1997. Now, that entire process itself is automated, and artists have become locked out of the production process entirely. Those reins on the artist have become chains. AI has been sent from 1997 to terminate the post-capitalist future.

Therefore, as Mark Fisher said so prophetically, there has been a “slow cancellation of the future” and in the time since 1997 – 30-odd years of cultural and artistic impotence characterised by irrelevant remakes, cinematic universes, band reunion tours, and endless nostalgia industry – he has been proved depressingly correct. Nothing new has penetrated the cultural zeitgeist that has irrevocably shifted the status quo of capitalist realism that the Thatcherite forms of neoliberalism perfected. Even while the broader political pendulum swings between the pervasive neoliberal consensus of 1997 and the reactionary fascism that it brings about, it exists as part of a fractalized political economy that continually gravitates around the original appropriation in 1997 of culture by neoliberalism. Those fractals become ever more nuanced with the introduction of AI, given that it scrapes existing images, text, video – often without the permission of the artist – to replicate the images, words, and films that the prompts ask it to. Hence the automation of banal artistic production that AI has ushered in has done away with any semblance of newness that might have been present with human artists, instead producing a future that is a highly complex, algorithmic, and machinic, but ultimately simply a continual rearrangement of the present. Hence, we are doomed to be administered palliative reruns and remakes until capitalism has metastasized into a season ending climate catastrophe.

Material matters

The key to escaping 1997, and to enter the twenty first century that we were promised, is therefore not to try and battle neoliberalism for the future (that is a battle that cannot be won as the fight is rigged anyway), but to smuggle the very real practices of artistic materiality from the past. This is more than simply working with our bodies artistically (and hence removing the threat of AI), to think this is to fetishize corporeal artistic practices. Instead, focusing on the materiality of our collective cultural practices means leaving something tangible and visceral in the world that affects it: an object, an echo, a vibration, an experience.

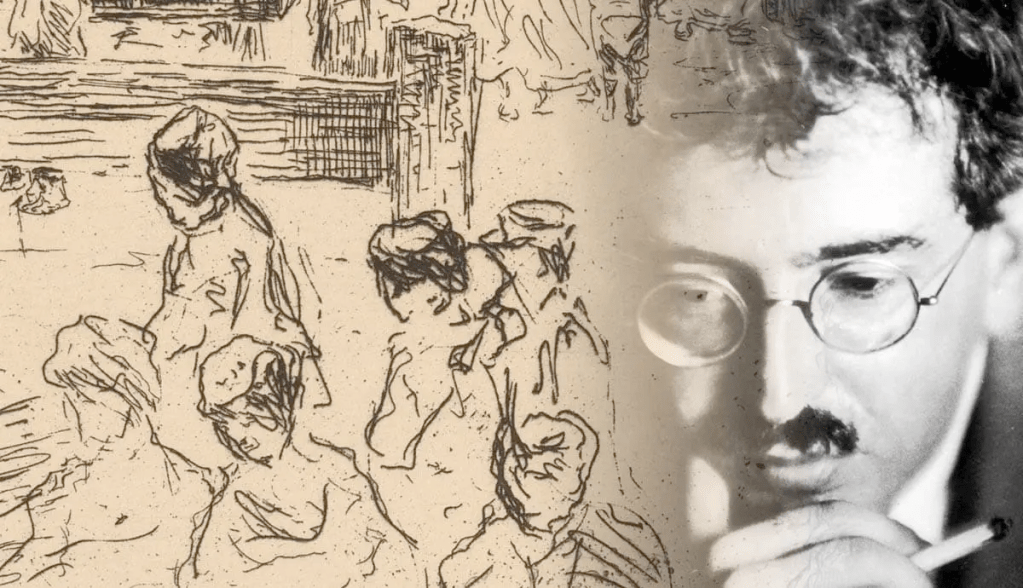

Walter Benjamin can help us understand this when he argued that in pre-modern (read pre-capitalist, or at least, pre-industrial) times, art held an ‘aura’, a unique, almost mystical quality that was tied materially to its place and creation in time and space. The aura of a painting, a sculpture, an image, or a text was intrinsically connected to the artwork’s singularity, its creative process, and its embedded history as a single, authentic object. It was in many respects, anti-technological.

An approach sympathetic to this Benjaminian view may perhaps signal a form of neo-Ludditism, recovering manual crafts, analogue technologies and even a revivification of revolutionary practices of Situationism, Surrealism and their ilk. Maybe that’s needed. But refusing technology will only go so far. As Fisher argued in Acid Communism, there is a materiality in the consciousness of revolutionary thought. He was arguing for a revival of the psychedelic culture precisely because it was uncapturable by the neoliberal machinery. He argued that “despite all the mysticism and pseudo-spiritualism which has always hung over psychedelic culture, there was actually a demystificatory and materialist dimension”. For Fisher, there was indeed a subversive potential to contemporary culture (i.e. that which exists in the pervasive present of 1997) if it can only navigate the alluring, yet dangerous, tentacles of neoliberal appropriation. He saw many subcultural movements such as rave, punk, hip-hop, arthouse cinema and even individual artists able to do this because they had a material aspect. Within rave culture, its emancipatory potential came about by people being together, often illicitly in abandoned warehouses, taking illegal drugs. Punk wasn’t just about the music, it was about tangible phenomena like fashion, the venues, the styles, the very human way of interacting with each other (by famously swearing on TV). Even the newer music genres of grime and dril rely on a distinct connection with place, often a stigmatised urban territory.

For Fisher, the beating heart of any subculture was its potential to serve as catalysts for emancipatory social transformation, albeit on a ‘small’ (personal, local or urban) scale at first, but with the power to echo through society. The gatherings and expressions of like-minded subversives, whether through underground music scenes, radical artistic communities, hackers, or cyberpunk collectives, were not isolated phenomena. They were dynamic material microcosms where new forms of resistance and resilience took shape. Subcultural spaces, mostly in the Western urban environment (notably around Southeast London where he taught in Goldsmiths) incubated innovative paradigms of thinking, collective identities, and modes of critique. These, he fervently believed, were the building blocks of a new social order.

Escape

1997 saw the imposition of neoliberalism into art practice, the marketing of the creative industries as a global policy initiative, and the professionalisation of culture as a financialised incentive. In so doing, it nullified the very DNA of art, that of human emancipation, political fermenting, and revolutionary potentialities. It then unleashed AI onto the world to eradicate that potentiality completely.

1997 leached the very materiality of artistic practice from us. Reclaiming it represents an act of resistance, a way to reconnect with the elements of creative practice that are yoked in human experience, emotion, and interaction. By reasserting the material value of the tangible over the virtual, the emotive over the commodified, and the common over the individualized, the public over the private; maybe we can begin to escape the 1997 neoliberal time loop we’re stuck in.

Leave a comment