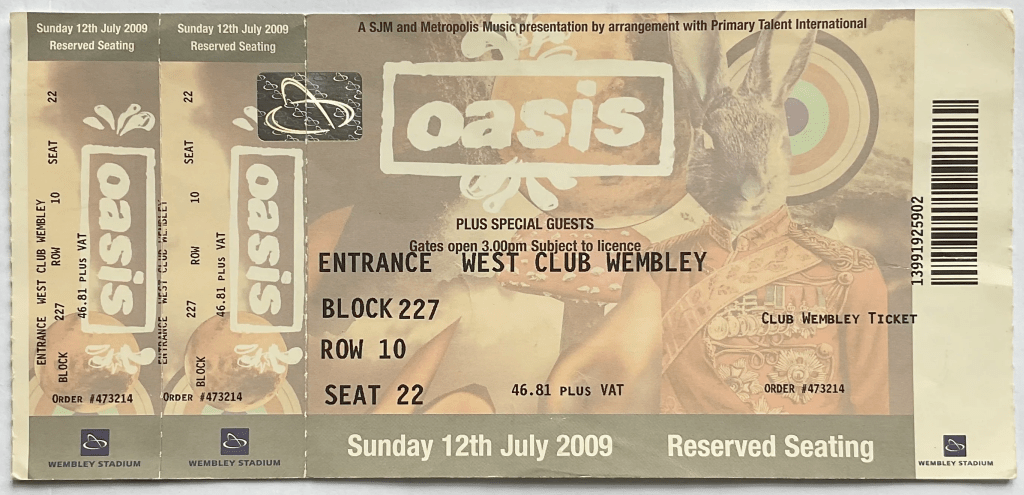

Were you involved in yesterday’s Ticketmaster fiasco around Oasis tickets? I was. I queued for nearly 7 hours, only to be booted out at the end as I was accused of being a bot. Luckily, I was part of a group of us all trying to secure tickets, and one of my friends was successful, but of course he had to pay the inflated ‘surge demand’ level prices….

As I was queuing patiently though, I was drawn to how the whole process is a microcosm of broader social ideologies clashing in the realm of what we can broadly think of as digital capitalism, or perhaps specifically what Nick Srnicek calls ‘platform capitalism‘. On one side, you have the deeply ingrained, almost anarchistic belief in the fairness of queueing, while on the other, there’s the cold, digitized reality of algorithmic and digitzed control and the ludicrous phenomena of ‘surge pricing’; a system designed to govern the allocation of scarce resources like once-in-a-generation concert tickets in a quasi-marketised way. When these two forces collide, the result is a chaotic intersection of ideology and technology.

Queueing is, at its core, a simple but powerful social construct. It’s based on the idea that everyone should have an equal chance, and that fairness is ensured by the order of arrival—first come, first served. There’s something inherently democratic, and yes anarchist, about this practice (which the whole cultural discussions around the queue for the Queen’s coffin, and scorn poured on those who jumped it, told us). Queuing requires no central authority to enforce (although maybe some infrastructure like velvet ropes); it’s a rule that we, as a society (albeit more so in the West), have tacitly agreed to follow. We line up, we wait our turn, and we trust that the person ahead of us in line is there because they arrived before we did (which of course, adds a temporal aspect to this mix). This self-regulating principle has been with us for centuries, and it taps into a deep-seated belief in fairness that transcends most cultures.

But in the digital age, the simplicity of the inate fairness of ‘the queue’ is at odds with the complexities of modern digitised technology. Ticketmaster, in its attempt to manage the overwhelming demand for Oasis tickets, relies on algorithms and third party computer software to govern the process. These algorithms and programs are designed to weed out bots and nefarious actors who might otherwise subvert the queue, securing tickets for resale at exorbitant prices.

However, the major critique that many people had of Ticketmaster was not just how badly the queuing system was managed, but also that the applied ‘surge pricing’ to late comers because of ‘high demand’. Tickets with a face value of £120 were being sold for £355 plus fees. Now, anyone who knows about the cultural landscape of this country could tell you that these tickets would be in ‘high demand’, and so how is this pricing mechanism any different to touting that they so vehemently guard against and despise? Applying this ‘surge’ pricing is a classic implementation of a neoliberal approach: i.e. using a marketised approach to implement ‘fairness’.

In 2017 when terrorists attacked Londoners near London Bridge, Uber experienced a surge in demand of scared citizens looking to escape the area. Of course, their algorithm noted this and upped the prices. Clearly to anyone with an ounce of empathy, this was grossly unfair, and Uber ended up refunding people. But it speaks to the way in which algorithmic and technocratic modes of governance have come to replace human intuition as a measure of ‘fairness’. Ticketmaster have done likewise. The ‘fairness’ of getting Oasis tickets, which people were willing to queue up for in the age old way that we attribute fairness with, were suddenly priced out of obtaining tickets.

This algorithmic governance (or ‘algocracy‘), for all its supposed efficiency, totally lacks the ability to understand the nuances of fairness as humans tacitly do. They operate on rules and parameters set by their capitalist creators, often prioritizing certain outcomes (namely profit) over others in ways that might not align with our traditional notions of equity.

This digital management of scarcity is a reflection of the implementation neoliberal ideologies. The market-driven approach to fairness, where ‘fairness’ is defined by the logic of the ‘the market’ rather than by the people affected by it, is alienating. It’s fairness outsourced to code, to a process that operates outside of human control. And this is where the tension lies. We’re asked to trust that these systems will be fair, but the opaque nature of algorithms, the impersonal nature of digital transactions, their fallability and the totally brazen profiteering process of ‘demand surge pricing’ often leave us feeling frustrated, angry and powerless.

Digital systems that manage everything from concert tickets to healthcare aren’t going away, so it’s crucial to examine how these systems align with our social values (which is why AI ethicists in corporations are so important, but currently so few are far between). The challenge is not about making algorithms more efficient, but about ensuring that they reflect the principles of fairness and equity that we hold dear; my fear is that if they are continually made under conditions of capitalism, they never will be. Because, in the end, the system is only as fair as the society that creates it.

The Oasis ticket fiasco is more than just a story about frustrated fans; it’s a snapshot of a broader ideological struggle that’s playing out across all aspects of our lives. It’s a reminder that, as we move further into a digitized world, we must remain very vigilant about how we define and implement fairness in ways that resonate with our deeply human instincts for justice and equality.

Leave a comment