Anyone who has sat through one of my lectures on cities will be sick of hearing that the built environment is never a politically neutral plane. Architecture and urban planning have always served as tools for political ideologies, shaping not only skylines but also the societies that inhabit them; and in an age of capitalist realism, the city’s physical form is its manifestation.

However, with a Trump administration redux to come next year, one question looms large: what might his capitalist-cum-authoritarian tendencies and narcissistic aesthetics of tacky gold leaf, neoclassicism, and overt architectural subjugation mean for the future of architecture and cities in America? It may have passed you by in a throng of unbuilt border walls and kids in cages, but Trump’s previous tenure saw the release of an Executive Order to “Make Federal Buildings Beautiful Again” which was a perverse dictate that viewed architecture not merely as functional or aesthetic, but as an ideological weapon in which to subdue the masses.

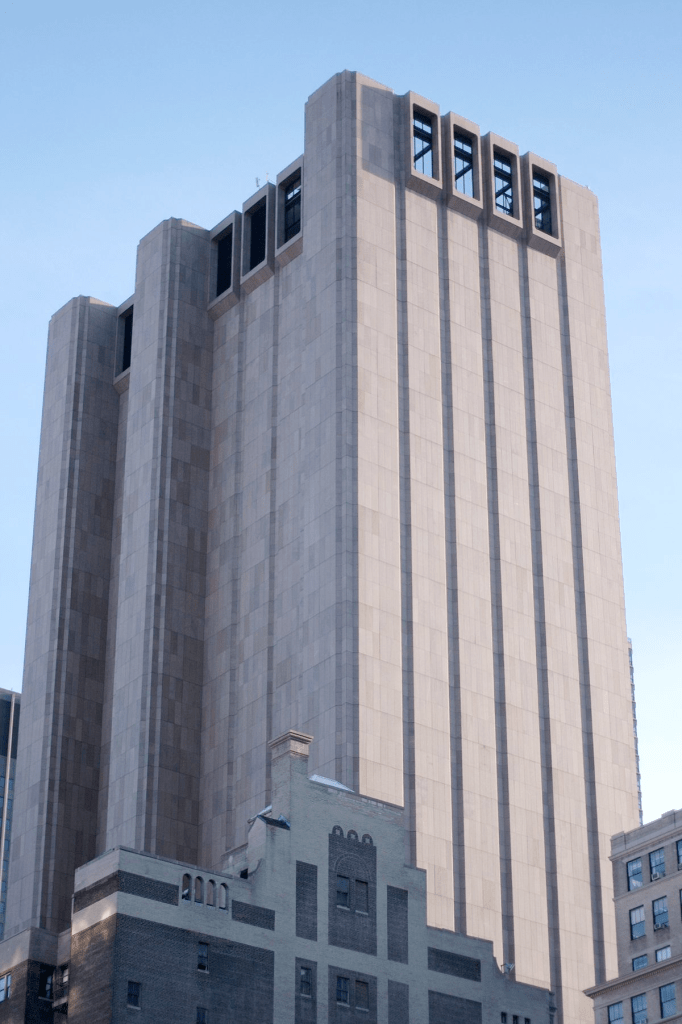

This 2020 Executive Order mandated that any new federal buildings should predominantly adopt (neo)classical styles, rejecting modernist approaches (like the imposing brutalist form of the NSA building in Manhattan) in favour of Greco-Roman forms of imperial might. Framed as a populist move to align public buildings with what he (wrongly, of course, but no less pig-headedly) saw as the aesthetic tastes of the American people, the Order evidenced a deeper ideological undercurrent of fascism.

Classical architecture, with its symmetry, monumentality, and emphasis on grandeur, craftsmenship, and a temporal affectiveness of Empire, has of course historically been appropriated by totalitarian regimes to project and manipulate power, order, and control. Indeed, Walter Benjamin, in his treatise on aesthetics and fascism – ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction‘ – saw this when he argued that “the distracted mass absorbs the work of art. This is most obvious with regard to buildings. Architecture has always represented the prototype of a work of art the reception of which is consummated by a collectivity in a state of distraction. The laws of its reception are most instructive.” Architecture therefore can be used to convey power, rule and oppression far more tacitly than any other art form.

For example, Adolf Hitler’s chief architect, Albert Speer, designed the Reich Chancellery and other structures to dwarf the individual, emphasizing the might of the state over the citizen. The grandeur of the ill-fated Germania (pictured above) was another case in point: it had the ideological pomp of classical Rome or contemporary Washington DC, but the architectural and design striation of a more controlling totalitarian city (and the pillared frontage of many of these classical designs has more than a whiff of the Antebellum architecture of the plantation and all it’s racist connetations). Speer’s monumentalism drew heavily on classical forms, evoking a continuity with the Roman Empire and its imperial connotations. Similarly, Mussolini’s EUR district in Rome (pictured below) fused classical and modernist styles to glorify the fascist state and its demand for ideological purity. The focus on axial symmetry and monumental scale was meant to communicate stability and unity.

Of course, it’s easy to see why fascists like Trump hate modernism; they reject the experimental, decentralized ethos of it, which he himself has linked to socialism. He has derided modernist architecture as alienating and elitist, aligning himself with a reactionary impulse to equate the avant-garde with political and cultural degeneracy. This is of course not limited to Trump nor strictly fascist ideologies; the ‘classic’ versions of UK liberalism is not immune to this thinking, stemming from our monarch and culminating in the nefarious Conservative-led think tank Create Streets.

The attacks on modernist architecture, with its embracing of innovation, abstraction, and the playful, often unserious, rejection of historicist styles, became a convenient target for authoritarian regimes looking to imprint themselves onto the city and rebuild it in their image (even more ire is of course focused on post-modernism with it’s percieved lack of universality and truth, two idioms that fascism has to purport to the fullest).

Such a rejection of modernism is of course aesthetic and ideological. Modernist architecture – and it’s many left-leaning, socialist and Marxist architects – often reflected values of openness, experimentation, the human scale and diversity, embodying the kind of pluralistic, heterogenous and experimental society that authoritarian regimes seek to suppress. Trump’s preference for neoclassicism, like many other historical autocrats, signals an attempt to impose a singular, monolithic vision of cultural identity, one that aligns with his broader nativist and nationalist rhetoric.

Clearly, Trump 2.0 will presumably have bigger fish to fry that federal architecture. I doubt the MAGA mandate had the destruction of brutalist architecture high on its list (although, not too far down for sure). But what they do have a penchant for is suburban expansion over urban densification (which they see too often as harbouring the ‘metropolitan elite’), championing car-centric development instead of 15-minute or walkable cities and opposing co-ordinated efforts to address housing shortages or climate resilience in favour of a general urbanism that embodies white supremacy. Trump’s urban policies reflected a classic nostalgia for mid-20th-century suburban sprawl, which prioritized privatisation and the nuclear family over public spaces and collective solutions. This ideology is evident in his campaign rhetoric that involved rollback of environmental regulations and his opposition to affordable housing initiatives.

Urbanists, architects, and planners must be prepared to resist this urban Trumpstopia. History shows us that architecture can also serve as a tool of resistance. From the informal settlements of the Global South to the participatory design movements of the 1960s, through the Occupy movement’s use of private squares in The City, as much as architecture can affectively suppress, it has the material potentiality to challenge authoritarianism and empower disaffected communities. In the face of a reactionary aesthetics and ideology, progressive architects and urban planners will need to advocate for designs that reflect the diversity, adaptability, and inclusivity of a democratic society; all the things that Trump hates.

Leave a comment