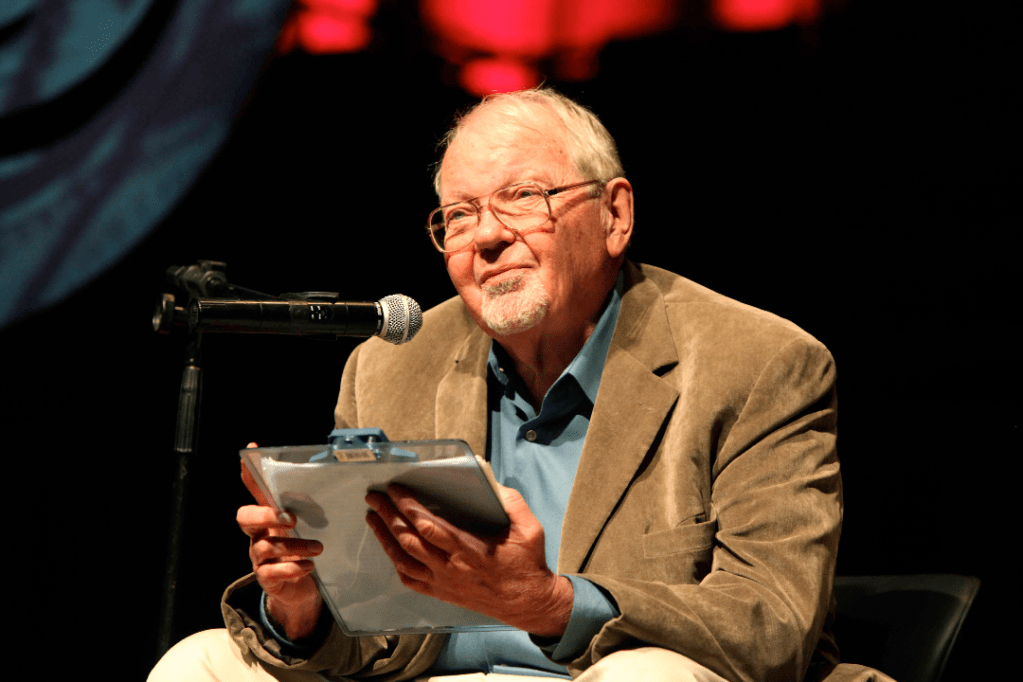

Over the weekend, while many of us were undoubtedly enjoying the fruits of the cultural conditions of late capitalism (be that at a theme park, out with friends not seen for years, or simply sat in front of the TV or social media), the main architect of our nuanced understanding of those conditions, Fredric Jameson, passed away at the age of 90.

Fredric Jameson was one of the most influential and prolific Marxist cultural theorists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and certainly found his way onto my reading lists at a very early stage of my career. His work spanned critical theory, literary analysis, political economy, and cultural studies, with his most pointed contribution focused on describing, analysing and critiquing postmodernism. Central to Jameson’s intellectual might was his imperious and peerless examination of how cultural forms both express and are limited by the socio-economic capitalist conditions under which they arise.

His early work introduced the idea that all cultural production is ultimately politically charged, even when not overtly so. In so doing, he foregrounded much of the narratives of the contemporary culture wars, in which any public figure in sports, media or basically any non-political career who dares utter a political opinion is castigated and told to “stick to football/music/TV etc”. Of course, such instruction is futile because for Jameson, literature, art, music, culture and even sport contain a ‘political unconscious’ that reflects the contradictions and conflicts of the social and often unjust structures they emerge from. For Jameson, literary and cultural analysis was not just a formal or aesthetic task, but necessarily a political one.

Skilfully combining Marxist historicism with psychoanalysis, he argued that every and any text can be read as a ‘socially symbolic act’, a manifestation of deeper class conflicts or the historical and pervasive contradictions of capitalism. Cultural works are always therefore ideological in their attempts to negotiate, subvert or even ossify the relations of capitalism.

But he perhaps is best known for his analysis of postmodernism, most notably in Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. In this work which I was introduced to in my undergraduate degree, he expertly theorizes postmodernism as not merely an aesthetic or philosophical movement, but the dominant cultural mode of late capitalism that was fragmentating any semblance of cultural or political meaning, collapsing historical consciousness, and birthing consumer culture as the dominant force shaping subjectivity. In many ways, Jameson’s work here was the natural child of Debordian critique of The Spectacle.

Jameson identified features characteristic of postmodern culture including pastiche, depthlessness, the waning of affect, and perhaps the most pertinent of all, nostalgia mode. He posited that this was the fascination with recreating past styles and forms, reflecting not only a crisis in historical understanding, but a paucity of creativity and the pervasiveness of capitalist realism. Given that today, our collective zeitgeist seems stuck in 1997 and doomed to repeat this ad infinitum, Jameson’s work was remarkably on point given he wrote it in 1991. In the absence of grand narratives or historical consciousness, for Jameson, postmodernism reflected the fragmentation of social life and the alienation of individuals under globalized capitalism. Anyone with even a remote understanding of Jameson’s work would therefore be ablet to see how the Right’s insipid and overtly incorrect critiques of postmodernism are laughably impotent.

As a geographer, Jameson’s more relevant theoretical contributions was the concept of cognitive mapping, in which he introduced as a way of resisting the disorienting effects of postmodernism. Riffing off Lynch’s seminal work on ‘mental maps’, mapping is a metaphorical process in which individuals develop an awareness of their socio-political position within the complex ensnaring webs of global capitalism. It is Jameson’s attempt to offer a form of Marxist class consciousness in an era where traditional forms of political organization and resistance have broken down (something which was picked up in the literature of the ‘post-political’).

Like many of the ‘big names’ of the cultural critiques of capitalism (big in terms of their appearances on university reading lists in the 90s and 00s at any rate) Debord, Baudriallard, Fisher and Deleuze, Jameson’s work can be read with a rather depressive affective register. However, a recurring idea in Jameson’s thought is the utopian impulse, notably in his work ‘Archaeologies of the Future’ from 2005. Postmodernism, because it necessitates fragmentation and a complete lack of meaning, ideology and/or politics, it can often seem to negate the possibility of utopian thinking. But Jameson identifies in certain cultural forms a repressed desire for alternative futures. For him, even dystopian narratives can be read as expressions of this utopian longing. His approach to utopia is nuanced and so resonates with my own understandings: he viewed utopia not as a blueprint for a perfect society, but as prefiguration – a way to imagine and practice alternatives to the present and to resist the ideological closure imposed by capitalism realism.

Like many great scholars he invited critique. Some have argued that his analysis can be overly deterministic or dismissive of the complexities and potentials of postmodern art, while others, such as Terry Eagleton, have sometimes found Jameson’s approach too abstract or insufficiently grounded in political praxis. Despite such criticisms, Jameson remained a towering figure in cultural theory. His ability to synthesize complex philosophical traditions (Marxism, psychoanalysis, poststructuralism) with incisive cultural critique has made his work indispensable for understanding the dynamics of contemporary culture under global capitalism.

For a professor who worked across most of the top universities in the United States, his work was grounded in an understanding of culture under capitalism. He is often attributed the phrase “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world, than the end of capitalism”. While his end has sadly come before the end of capitalism, undoubtedly his intellect and written word have not only aided in our understanding of it, but also given us some tools with which to dismantle it. RIP Fredric.

Leave a comment