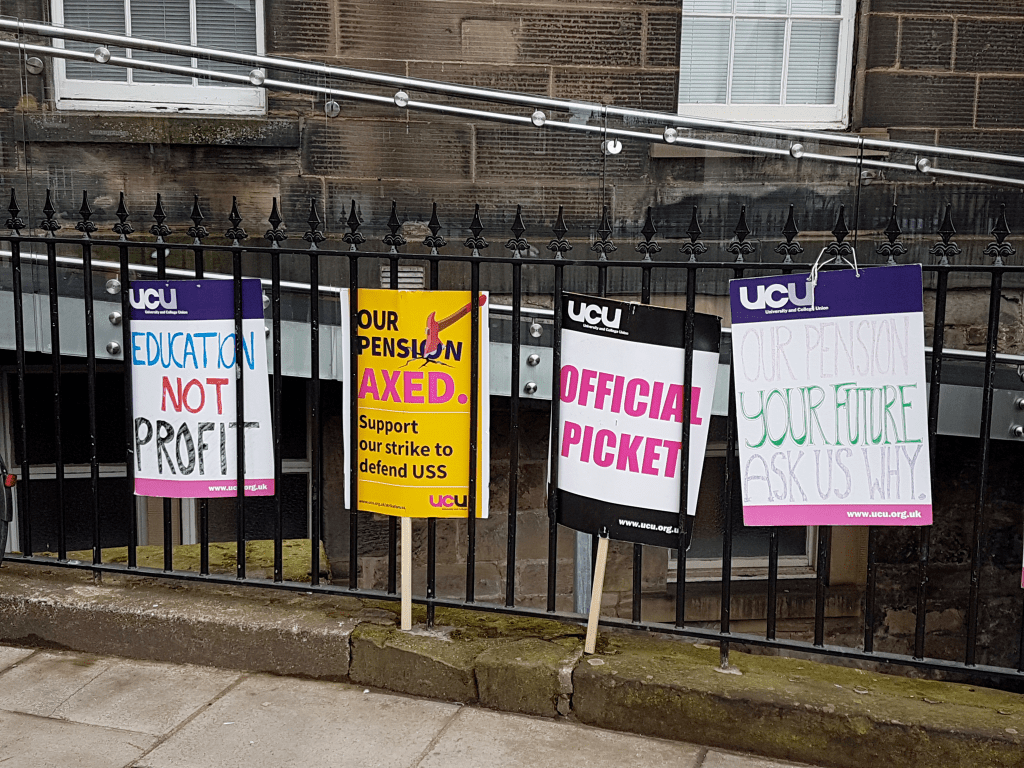

UK higher education (HE) is undergoing a profound and deeply unsettling crisis. Universities across the country including Newcastle, Cardiff, UEA, Dundee and many others (seemingly by the day) are shedding staff, closing departments, and strikes are taking their toll. The sector is in a state of managed decline, and the atmosphere within institutions reflects this reality: disillusionment among staff, declining morale, and acute financial precarity are now commonplace. The causes are both structural and political, but they are not inevitable. This is a manufactured crisis, produced by decades of neoliberal policy, short-term managerialism, and a persistent failure to treat universities as what they are: prized public assets that enrich our culture, society and economy.

At the heart of this crisis lies the aggressive marketisation of higher education over the past thirty years (since Blair’s Higher Education Act in 2004). Since the introduction of tuition fees and their subsequent tripling in 2012 by the coalition government, UK universities have increasingly operated like corporations: investing in extensive branding exercises, engaging expensive management consultants, expanding middle management layers, and undertaking costly campus redevelopment projects, often funded through unsustainable levels of borrowing. Meanwhile, the core missions of teaching and research have been hollowed out. Staff workloads have ballooned, secure contracts have been replaced with casualised labour, burnout is at an all-time high and academic freedom has been compromised by draconian culture war politics.

More recently, the economic context has worsened dramatically. Tuition fees have remained essentially frozen in nominal terms since 2012, amounting to a real-terms decline in income for universities. Inflation, surging energy costs, and elevated interest payments, exacerbated by the fallout from Liz Truss’s catastrophic 2022 mini-budget, have further squeezed institutional budgets. On top of this, international student recruitment has faltered, in part due to hostile immigration policies and the Home Office’s erratic stance on student visas and dependents, even under Labour’s new government.

In response, universities have turned to blunt instruments: redundancies, programme closures (especially in the arts, humanities, and social sciences), and asset stripping. These measures are self-defeating. They degrade the student experience, diminish the intellectual capacity of the sector, and do long-term damage to the UK’s international reputation for higher education.

While a comprehensive overhaul of HE funding is necessary, there are three immediate, cost-neutral policy interventions that a Labour government could implement to stabilise the sector and buy time for more ambitious and radical reforms. These would not resolve all structural issues, but they would provide the breathing space urgently needed.

1. Reinstate Student Number Controls Across the Sector

The removal of student number caps in England – initiated by the coalition government in 2015 – was ideologically driven, premised on a belief that market competition would drive up quality. In practice, it has allowed elite institutions, particularly within the Russell Group, to aggressively expand their undergraduate cohorts by slightly lowering entry requirements. The resulting ‘arms race’ has drawn students away from mid-tier and post-92 universities, leaving these institutions under-enrolled and financially exposed.

Restoring number caps would rebalance student distribution across the sector. Moreover, tying these caps to staff-to-student ratios would create incentives for universities to maintain adequate staffing levels if they wish to grow. This is a simple regulatory mechanism with profound implications for quality assurance, employment stability, and equitable sector-wide planning.

2. Suspend the 2029 Research Excellence Framework (REF)

The REF, while originally designed to allocate public research funding based on merit, has become an overly bureaucratic and resource-intensive exercise. The preparation for each REF cycle consumes vast amounts of academic and administrative time, distorts research agendas, and often privileges short-term metrics over long-term intellectual contributions.

With government research funding already declining in real terms, with rumours of £100 million worth of cuts, the next REF (scheduled for 2029) represents a disproportionate use of scarce institutional resources. Suspending the next cycle and extending the current REF status until 2036 would immediately free up time, reduce costs, and ease workload pressures—especially in the humanities and social sciences, which often fare worse in REF’s narrow evaluative criteria. The same applies for the TEF and the KEF.

3. Reverse Restrictions on International Student Visas and Dependents

Recent policy changes aimed at reducing net migration (such as restricting the right of international students to bring dependents) have had a catastrophic effect on enrolment, particularly from postgraduate students outside the EU. These policies are not only economically self-sabotaging (given that international students cross-subsidise UK students and research), but also ethically troubling, sending a message that global scholars and their families are not welcome.

Lifting these restrictions, particularly for postgraduate and PhD students (who pay more for the privilege) would both restore the UK’s attractiveness as a destination for international study and mitigate the short-term revenue crisis many institutions now face. Additionally, targeted recruitment of students fleeing authoritarian crackdowns, such as those under Trump’s anti-intellectual and anti-university policies in the United States, would align with the UK’s global democratic commitments and bolster academic freedom.

—

These three measures are entirely cost-free for government. They do not require new spending commitments, nor complex legislative change. What they demand is political will, sectoral understanding, and a recognition that universities are more than businesses; they are foundational to a democratic society, economic innovation, and cultural vitality.

The long-term solution to the crisis in UK higher education must involve a wholesale reassessment of how the sector is funded and governed. But in the short term, these pragmatic steps would offer immediate relief and create the conditions for a more just, sustainable, and intellectually rich university system. Any future government serious about education, social mobility, and the knowledge economy must act: and do it urgently.

Leave a comment